Botanical Gardens Second episode

Jahawarlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute

As Dr Abdul Jabbar and I left the collection of different species of palms I thought about the elephants that roamed the gardens at night, eating the young, tasty palm trees, trunks and all, right down to the roots.

“Yes,” he said, “they’ve eaten several palm trees. We have to keep replanting.” He smiled. “This garden is in the middle of the forest so we have to work with everything, including all the animals that live in the forest.”

At this point we came to the orchid house.

“I see you protect the orchids,” I said. We stepped inside.

“This is the Indian pitcher plant,” he said. “The only one. This clever little plant emits blue fluorescence, invisible to us, but very attractive to insects, which enter. It then emits carbon monoxide and the insect begins to hallucinate, falls down and cannot escape the downward-facing hairs inside the plant.” He then showed me another pitcher plant.

“The whole leaf is a pitcher in this case,” he said, “whereas it’s the stem that’s modified into a pitcher in the Indian plant.”

We looked at several other insectivorous plants and some rather ordinary orchids. I realised that it was not the flowering season for the rare orchids.

“Kew Gardens are associated with us,” he said, “but only for the orchids.”

We left the orchid house and headed to the Medicinal Plants Demonstration Garden.

“In Ayurveda they use four species of Ficus together: Ficus racemosa, F macrocarpa, F religiosa and F bengalensis,” he said, pointing to the plants, all growing together in a little clump, “to treat women post partum. It doesn’t work if one of the four is missing and of course if you buy the mixture you can never be sure that all four plants are in it.”

It seemed that in Ayurveda each remedy included several different plants.

“On the other hand,” he said, as we moved along the garden, “allopathy (regular conventional western medicine) focusses on one compound from one plant at the time.”

We were looking at Vinca rosea, the Madagascan periwinkle, from which vincristine has been isolated and is used to treat cancer patients. I knew all about this, but I’d never seen the plant before. It was a rather nondescript little pink flower.

“Dioscorea … Rauwolfia,” he rattled off, as we looked at other plants used in conventional medicine. “And here are a few examples used in homeopathic medicine,” as we looked at some small, green, leafy plants.

“Tribal medicine is important,” he said, as we inspected Pterocarpus marsupia. “Tribals cut the trunk to make into a cup and store water in it overnight. In the morning they drink the water to control diabetes.”

“There are 1,168 species of medicinal plants in this part of the botanical garden,” he said proudly, as we descended some steep steps. “Careful now,” aware that I’d already managed to scrape a layer of skin off my knees that morning.

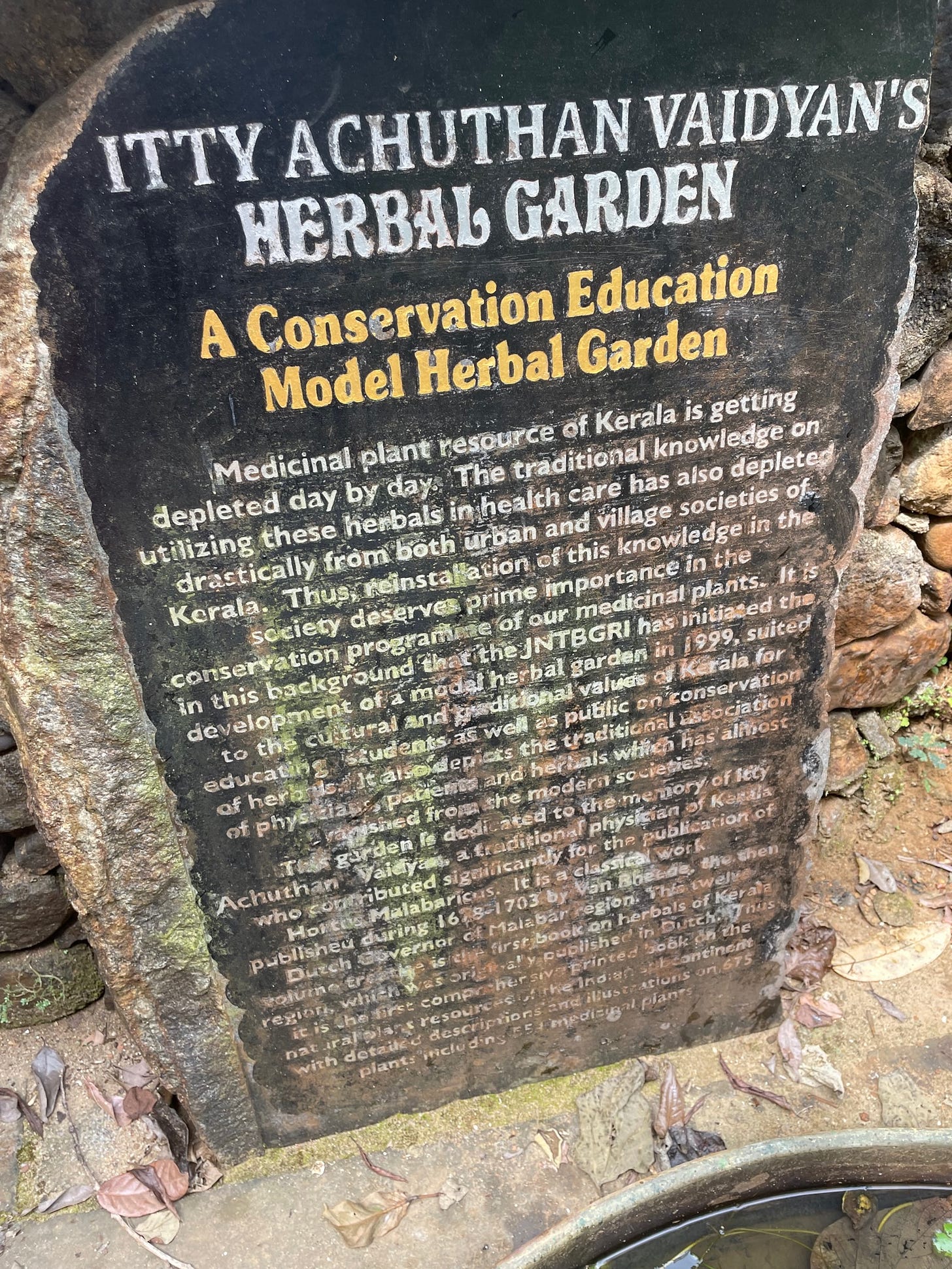

After walking through fields of medicinal plants we came to Itty Achuthan’s Garden, or rather a replica of it. Itty Achuthan (or Achudan), lived in the late 1600s was a physician and herbalist who recorded traditional knowledge of the local medicinal plants in Hortus Malabaricus, with the help of the Dutch Governor of Malabar.

Jabbar took me to a shady little building where a life-size model of Itty sat in a chair with his hands raised. Jabbar put his arm between Itty’s hands to demonstrate how the physician would have taken the different pulses.

“He could diagnose exactly what was wrong with you,” he said.

“Yes I know,” I said. “I’ve experienced this pulse taking by an Ayurvedic doctor. And yes, he could tell what ailed me physically, mentally and emotionally.”

Hortus Malabaricus was published in Dutch after Itty’s death in Amsterdam between 1678 and 1693.

“There’s an English translation in our library,” Jabbar said, “but it’s difficult to read.”

Replica of Itty Achudan’s Garden